The Art Of Optimizing Small Biotech Market Caps – From Scientific Dreams To Strategic Reality

By Wayne Koberstein, Executive Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @WayneKoberstein

Last month, in Part One of this discussion, our panel of company executives and investment experts examined the key factors that can determine a small life sciences company’s valuation and market cap. As the sun rose outside the large meeting room window overlooking the San Francisco skyline, our roundtable — held during the confluence of industry events surrounding the JP Morgan Healthcare Conference in January 2014 — continued to explore the effects of valuation and market cap on such a company and what it can do to optimize its value at every stage of its development.

The remainder of this thought-leader discussion covered the effects of valuation and market cap on companies as they grow and on ways they can optimize their value at every stage in their development. More case studies and experience-based lessons arose in the next half of the discussion, along with worries about drug-candidate shortages and unsustainable investment cycles. Here, the panel detailed the importance of managing company and scientific communications, establishing relationships, spending cash carefully, and other actions companies can and should take to optimize their value and growth.

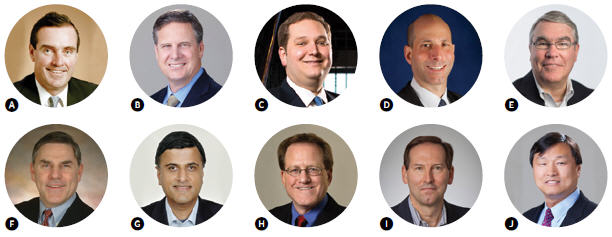

Our panel consisted of the following people — the ones who answered the invitations we had sent out to a range of people reflecting the leadership of small and large biopharma companies and investment firms:

A Dennis Purcell Senior Partner of Aisling Capital

B Rich Vincent CFO of Sorrento Therapeutics

C Jacob Guzman Corporate Client Group Director at Morgan Stanley

D Allan Shaw Managing Director at Life Science Advisory Practice, Alvarez & Marsal LLC

E Ford Worthy Partner & CFO of Pappas Ventures

F Kenneth Moch President and CEO of Chimerix

G Jaisim Shah CEO of Semnur Pharmaceuticals

H William Marth CEO of AMRI

I George Golumbeski Senior Vice President, Business Development at Celgene

J Henry Ji CEO of Sorrento Therapeutics

STAGES OF VALUE

Another case of start-up financing illustrates how a track record of credibility helps founders through the critical points of company valuation. But panelists still worry about the inevitable effects of the life science business cycle. The moderator turns to entrepreneur Henry Ji, CEO of the new start-up, Sorrento, for his view of early stage investment and valuation.

WAYNE KOBERSTEIN: Henry, how are companies affected by the valuation that they receive at any given point?

HENRY JI: I’m going to answer by describing some innovative ways we used to raise money at different stages. We were raising our money in 2009, during the financial crash, but we had no VC, because the VCs at that time were more realistic — they wanted only latestage programs. There were no earlystage dreams; you cannot sell dreams, with only a patent in hand. So we went to individuals and groups, basically. We went to the experts in the therapeutic antibody field because we were building our own therapeutic antibody library. We went to the father of the human antibody library, the inventor for the catalytic antibody library technology, who is Richard Lerner. He liked our dream, and he picked up a phone to call Phil Frost. That’s how we got our main investor, who never worried about the financial crash.

Phil put us into a shell company, with the valuation fluctuating from $10 million to $400 million, when we had about 300 million shares outstanding, so we would not know what our value was. That was easy to sell to our initial investors, but not to the VCs, which is why we didn’t have any VC investors at first. So it was a tough one — selling a dream — especially because we didn’t even have a clear strategy yet, only the dream of building the antibody library.

A couple of billionaires were the first ones who funded us. We started our dream with a $10 million valuation. At that point you have to figure out how to really get going; that’s when the strategy kicks in. You cannot sell dreams forever. You have to be realistic. Last year, we did three transactions to help us transform the company from a discovery company to a late-stage oncology development company. We were looking for some early leads into new therapeutic antibodies, but that takes a very long time, so we bought a late-stage oncology product that is a next-generation formulation of paclitaxel, Cynviloq, and a Phase 1/2 cancer-pain management product, resiniferatoxin, and strengthened our antibody platform with ADC or antibody drug conjugates platform, making us the leader in the ADC space.

VCs are tough to talk to because they are very realistic. You know, they want to see the data, preferably late-stage data. In between the early investment and seeking venture capital, we had an alternative strategy. We went to China. Most of the time, Chinese investment is relationship-based. Once you establish a relationship with the Chinese investors, the valuation is much easier to build. The beauty of this strategy is it gives us alternative resources to what we have here in the United States, where the valuation is very low. So now we’ve got a decent valuation, we have our money, we can move our program forward, and we can continue to do some transactions. That helps a lot. Without the valuation, we could not do some of the deals we have done on the acquisition side.

KOBERSTEIN: So, at what point does valuation and market cap become important in a company’s development, and in what ways does valuation affect how a company develops?

PURCELL: There comes a time in every company’s evolution — when the stock is high, you sell the stock, and that relates to the cost of capital. It’s a very interesting question, again, with Intercept; they can sell two million shares and raise a billion dollars and be like one of the biggest companies in the world, at least for a day. So when the valuation goes up like that, you’ve got to figure out a way to take advantage of it.

SHAH: And you maximize that by saying that the sky’s the limit, or do you try to be cautious?

PURCELL: One of the things I’m worried about is that we’re in a great period right now; this is a big time for biotech, but we’ve also been through years and years where companies have only six months of cash left. When there’s less money, the optionality goes away. I would give three main pieces of advice to companies: One, right now, when you’re well-capitalized, pretend like you only have a month of cash left so you don’t waste the cash. Two, I believe we have to reassess governance at these companies. We talked a little bit before about the business versus the science — get the right board members. And three, now is a good time for companies to develop more options for where you might take the business going forward.

SHAH: But isn’t it great that we can see this turnaround?

PURCELL: It’s relatively consistent.

SHAH: It is amazing how quickly the general climate can turn around, right?

PURCELL: Well, here we are at the beginning of the year and everybody’s euphoric — there are 33 companies trying to press for an IPO in the next 30 days. But this thing could turn on a dime.

KOBERSTEIN: As does the chatter that goes on in the press . .

PURCELL: We may have 100 companies trying to get out in the next two months, so that’s got to create a bit of an issue. The class that went public in ’13, they’re all good companies. The question now is, are we moving down to the second tier of companies? And what does that mean? Their investors are just going to get tired.

MOCH: We’re hoping to differentiate. In a way, your second-tier theory is logical, but it remains to be seen.

PURCELL: Already, as we saw toward the end of the year, the generalist investors have started to get out of the sector. In December, we saw stocks trade down, and a lot of that has to do with the generalist investors leaving. We are all looking to see what happens to the next 30, 40, 50 companies that are trying to do an IPO.

MOCH: The essence of it all is that nobody has ever invented a cure for the business cycle.

PURCELL: But that’s what we have to do; we have to figure out, as an industry, how to stop this vicious cycle. It would be so valuable for everyone. But we’ve been saying that for 25 years.

MOCH: The quandary will not go away because it’s a requirement of the SEC that we release such information. Remember, this is one of the few industries where, because of the long timelines to develop a product and the requirements for capital that go with that, everything is public and everything matters, which is why we’re always watching dramatic fluctuations in company stocks. A public company has a material obligation to disclose that it just did a small Phase 1 trial that had six patients who performed well. If you don’t let that information out, you get to go to jail for withholding material information that could affect your stock price, and so it does. At a Big Pharma, you would say just let it stay deep in the bowels of the company, but for a biotech company with a small number of people, it is the key material event dictating the future.

KOBERSTEIN: Okay, let’s say I’m a small life sciences company, Koberstein Biotek, and all of the megatrends and movements we’ve discussed affect me — the business cycles, booms and busts, and other external factors. But what about the factors that are peculiar to my company? I want to know what I can do to influence the valuation of my company and make it what I believe it should be at any given stage. Is it about getting enough press? Is it about getting my story out? Is it about networking with others in the same sector?

MOCH: I’d like to see what the investors say about this, but I think the biggest influence on probability of success is what Dennis was saying — it’s having capital — and everything else flows from that. I do believe in the capital-asset pricing model. If you look at all the risks for a company, the biggest risk is lack of capital. As Brook Byers [senior partner, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers] said many years ago, “The greatest challenge for a CEO is not that a trial doesn’t work, it’s not having the capital to prove that it might have worked.” I’ve always liked that statement, because that’s our job. Gathering enough capital to conduct the best possible clinical development. There is the vision; there’s talking to people, there’s making noise and being heard, having 50 meetings in four days, and all that — but if you don’t have the capital that gives people the confidence you can get through to the end of the experiment — the clinical trial — then nobody really cares. Having the capital to get to something is different from having something. That’s the interesting dynamic of this business.

SHAW: To underscore Ken’s point, too often companies try to time the market when they access capital, and I don’t believe this should be done. When the ducks are quacking, you have to feed them. You have to seize the opportunity. People get stuck looking in their rear view mirrors at yesterday’s valuation; they don’t look ahead at the opportunity, and it passes them by. One company had a nice run-up in valuation and became fixated on reading their press clippings, believing their product would go forward with an accelerated approval and thinking maybe it would raise its money then. And my advice to them was, don’t time it. Just take it when you can take it. And unfortunately things did not evolve for them as hoped, and their valuation slid back down again. So yesterday’s value now looks a lot better than today’s.

PURCELL: We see that a lot. Companies come in and say, our pre-money is $100 million, period. So, we say, “All right.” And nine times out of ten, they present again with much more reasonable expectations. I’ve got a little hint for your new company, Wayne. There are 8 million accredited investors in the United States and only 2 percent of them own a private placement. So my prediction is, because of the JOBS Act and because so many companies are starting up, crowdfunding will be important to your new company. You might raise your first $5 or $10 million not from VCs, but through the crowd, because it’s a huge untapped market, and there are companies now being formed to take advantage of that market. So that’s how you raise your money and get started.

GUZMAN: That’s an interesting point, because my clients are saying exactly the same thing, over and over and over again.

PURCELL: I see it coming.

GUZMAN: I’ve had so many attorneys and executives come to us looking at the untapped accredited investor market. Everyone from venture-backed companies to the large players like the Carlyles of the world. These groups are saying they know the institutional players well, and the accredited market is the one they’re focusing on next.

OPTIMIZING VALUATION — PATIENTS ON YOUR SIDE

KOBERSTEIN: Patient advocates, long the natural allies of companies with new treatments in areas of high medical need, are now taking a more direct role in value-setting investment.

WORTHY: The conventional wisdom is that you can probably start companies through crowdfunding, but when a company gets to the point that it needs to raise $30 million, as Jaisim did, that may be, and probably is, unrealistic. Wayne, you mentioned the press and the degree to which the press can play a role in affecting valuations. The press written about a particular company has everything to do with creating expectations. From many investors’ perspectives, what is said in the press that has information value is one thing, but in creating expectations that really affect the way that we’re valuing companies, probably there’s a minimal impact. However, it is important and in some cases critical for a company to manage expectations in the press very carefully. Companies that do it well can actually create value, but not in the way that you might imagine.

We are fascinated these days with the degree to which patient advocacy groups are beginning to play a real role in the development of drugs. The role involves bringing money or influencing money to come to the table, and it also involves raw political pressure. We saw it with Plexxikon, a company that we invested in a number of years ago. Plexxikon let a reporter from the New York Times be almost embedded in a long clinical trial it was conducting, and the Times came out with a fascinating three-day series on the trial. We believe the effect that this coverage had, not directly on investors, but on patients who were clamoring for this melanoma drug, and the way that this pressure and interest rippled into the FDA, through Congress, and so forth, positively and dramatically affected the speed with which the company got the drug approved.

We also believe the New York Times story lent a unique validation, in this case, particularly from the perspective of Japanese investors, and ultimately a Japanese company acquired Plexxikon. So it’s obviously important to manage expectations through what is disseminated in the press. It can be a two-edged sword, but that’s an example of how patient advocacy groups, through learning about a company through the press, can have an impact on the speed with which a drug is approved.

WRIGHT: The lesson is, if you want to improve your drug’s probability of accelerated approval, embed a reporter as a mediator variable to your clinical trial! (Laughter.)

MOCH: I’m on the board of BIO [Secretary, Emerging Companies Section Governing Board], and there’s a lot of discussion there about patient advocacy groups and bringing them more deeply into the process. I have no doubt you are seeing it day in and day out at Celgene, George, with the patient populations you serve. They want to be involved, they do help in fundraising and informing patients, and they have a voice with the regulators. There is no doubt they have a voice at FDA advisory committee meetings. They also have a voice in our particular drug-disease area where, because the conditions are lifethreatening, the drugs are allowed to be used compassionately. You’ll be shocked by the number — we have 430 compassionate uses — which a larger company wouldn’t do. It’s just the way we evolved. But we stopped that program because the FDA asked us to go out and collect all the clinical data from the compassionate-use patients, and it was costing too much, unfortunately. We still get 10 calls a week from doctors who want this drug. And clearly they’re also calling the FDA, which wants us to figure out a way to either deal with it or stop people from calling in all the time. But that type of clarity of unmet need is very important in the approval process. You can’t underestimate the voice that patients have.

KOBERSTEIN: I recently interviewed Janet Woodcock, and I asked her about the FDA’s implementation of accelerated review in specific cases, including Sarepta. She said something very similar to what I’ve heard here, which is it’s all about the data. She said there are so many companies wanting accelerated review now, and the agency is examining each company’s data, comparing it to the others. If the company’s data isn’t up to the same standard as another, it’s likely to be denied, no matter how intense the patient advocacy.

MOCH: That’s their job.

KOBERSTEIN: Yes.

MOCH: But patient advocacy still puts it on the FDA’s plate to make a decision or to review it. And patients do have a voice — whether the voice is good, bad, or indifferent. I’m sure you have a whole patient advocacy department in your company, George.

GOLUMBESKI: We do have a very strong advocacy group, and they will continue to be important down the line. In fact, they are very helpful in helping us remember what we are working for. But in the end, in my opinion, that will not get a drug approved. My own personal view is too many small companies spend too much time and lost motion deliberately trying to pump up their stock price. If I had a penny for every press release I’ve reviewed in my career based on 10 patients with almost a claim that DDMAC (Division of Drug Marketing, Advertising and Communications) would get on, suggesting there’s efficacy … I completely agree with everything Ken said, but just look at all the press releases saying, “We got an SPA [special protocol assessment].” That’s probably a material event, but it is relatively easy to get an SPA in a very high unmet medical need condition. And does that mean you have a drug? No, it means you’re going to do a trial. With cancer trials, 50 percent fail in Phase 3. I’m not saying they shouldn’t do a press release. But generally, trying to suggest that the drug is working after testing it in 3 or 30 patients is a mistake.

PURCELL: The multiple myeloma people have their own venture fund. So not only are patient advocacy groups going to be involved, now they will be starting their own funds.

MOCH: And they’re going to move from funding basic research to funding clinical development in big ways, across various areas.

GOLUMBESKI: A year ago, we started working closely with LLS, the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, and we also have a lot of interaction with MMRF (Multiple Myeloma Research Fund).

KOBERSTEIN: If it’s a group like the Prostate Cancer Foundation, they will have the right expertise in-house, but there are other groups that may not be qualified, so what you’re describing may be somewhat of a chaotic situation.

PURCELL: One of the questions on the investing side is, why should we reinvent the wheel on multiple myeloma? They know everybody. Why should we examine these companies one by one? Why wouldn’t the venture community partner up with the disease foundations, because they are the experts. They know everybody. They know what’s hot, they know what’s not. I think you’re going to see more of that kind of collaboration between the investors and patient advocates.

GOLUMBESKI: Some of these groups are run by really excellent medical directors, really smart people.

SHAH: It’s also not inconsequential. We were talking about the business cycle, when the capital markets and the venture funding is available and then not available. The patient advocacy groups will go a long way to bridging that gap as providers of a longer-term funding mechanism for innovation over time.

KOBERSTEIN: So, in other words, anybody who brings capital to the table is welcome, right? And you deal with the details later?

SHAW: I don’t think anybody who’s in need of money is going to pass it by, as long as it’s from a legitimate source.

KOBERSTEIN: The last question is, “What actions can companies take to achieve or optimize their market cap at the key stages of development?” You gave me some good points for Koberstein Biotek. Are there any other things my company can do that we haven’t covered?

MOCH: George was talking about it in an interesting way: Although we are required to communicate, it’s the quality of the communication that counts. But it’s not formulaic — how you write the releases is subject to interpretation, accounting for some of the things that make us all squeamish. Sometimes I get nuts when I see a company make claims early on in a press release, and its stock goes up, or they raise money. Is that really fair, versus a more conservative approach where you don’t get that bang? It is an enigma, because the market often reacts positively to creatively written press releases, and yet, they raise capital. And to come back to the earlier point, capital is the most important element in creating value and being able to get through development.

WRIGHT: To Ford’s point, the reason the trial he referred to had so much value wasn’t just because the New York Times reporter was there, but because it was somebody outside of the company serving as a witness. The lesson might be, who can you get outside of your company to start talking about your product?

MOCH: In his example, Ford was talking about an extraordinarily serious situation, which would boost the valuation.

GOLUMBESKI: We have to remember how brutally devastating metastatic melanoma is, and this was the first drug that worked in some patients. That is a pretty hard situation to ignore. But my point about stating early results — we may be seeing the issue illustrated now in the Novartis- UPenn collaboration with CART in B-Cell disease. Out of the first 10 patients or so, three or four of them were end-stage, and they’re in complete remission now. That has been in the New York Times multiple times, as it should be, because the results are truly groundbreaking, even if the number of patients is small.

A CEO I know once said, “I’ve raised money when I could, and I’ve raised money when I had to, and believe me, it’s a lot easier to raise it when I could.” We take the same attitude with respect to building our pipeline. The reason we’re so active now is none of us knows how long we’re going to be in this financial position, but we’re in a position where we can build our pipeline, and we have to do it now, because God help us if we’re trying to do it when we have to.

WORTHY: I was just going to say, my point was not to embed a New York Times reporter in every trial, but it was really the larger point of how good management of communications, not only with the press, but also through social media, can stimulate activity among patient advocacy groups.

MOCH: As an industry, we are going to figure out the right focus. The leadership at BIO is working right now on producing an industrywide view of the best practices for company engagement with advocates during drug development.

KOBERSTEIN: And likewise, this discussion we’ve had today is just a part of an ongoing industry conversation on best practices in creating value and seeing that value reflected in your company’s valuation and market cap. I thank you all for coming and for participating in this enlightening exchange. We will be presenting this discussion on-line and in the pages of Life Science Leader, and we will continue to take up the same topic in other venues in the future. Good day.